So here we find ourselves, the night before own big push on the front line of the stage “in his hands” (Milne, 1918). The night before our first performance of “Sincerely Yours” and for some reason I have not been going over my lines or my dance routines as relentlessly as I normally would. Instead, I have been drawn to the letters from the First World War boys again. And despite our performance being more focused on the roles, positions and states of the women during The First World War I find myself connecting with the women in the closest way by reading the letters that the soldiers sent home to their sweethearts, family and friends.

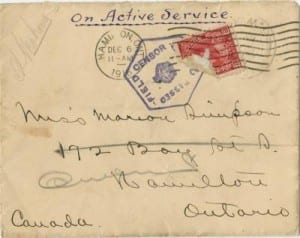

(Vaughan, W. McMaster University Libraries)

Some talk with passion and yearning, some with hope, some accepting of their fate before they even know it and some talking seemingly about nothing of deep meaning. However, it is these letters that are most interesting and arguably say far more than those men who literally spelt out how much they missed home. These men who were “quiet” in what they were saying, often commenting on the weather, that they were well and hoped their letter recipient was the same, or that they couldn’t say much. However, the recipients of the letters could find everything the needed to know and just how their boy was doing in the rows and rows of kisses that would fill the bottom of the page.

28th May, 1918,

Dear Father,

Just a few lines in answer to your letter which I received today.

Yes I got my food alright and you can have supper if you like to go for it, and you can bet I always go for supper. I am taking your advice and eating all I can.

I will see the officer about the allowance in a day or so, as I have heard today that two or three boys mothers are receiving an allowance, but I don’t know how much.

Well, I think I will have to close now. As I haven’t anything more to say just at present. Hoping you are quite well.

From your loving son,

Ted.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

PS. Love to Dolly and Frank

One of the roles that officers in the Great War had to fulfil was to read and censor every single letter sent back to England in fear that it might reveal some vital piece of information that would prove dangerous in the wrong hands. However, these rows of kisses was the one thing that would never be censored. The men and boys would expose themselves as to how much they loved the person they were sending the letter to, show their fear and longing to be reassured and generally that regardless of how little interesting content their letter had, they were alive and saying all they needed to in the rows of x’s. Some men would do kisses all over the bottoms of their letters and some even squeezing kisses up the sides of pages.

France, 24 March, 1917

My dearest Emily

Just a few lines dear to tell you I am still in the land of the living and keeping well, trusting you are the same dear, I have just received your letter dear and was very pleased to get it. It came rather more punctual this time for it only took five days. We are not in the same place dear, in fact we don’t stay in the same place very long… we are having very nice weather at present dear and I hope it continues… Fondest love and kisses from your

loving Sweetheart

Will

xxxxxxxxxxx

And a common theme would be that their fate was “out of their hands”, “in the hands of the Lord”, they could not foresee what was going to happen but “all [they could] do was put [themselves] in God’s hands for him to decide” (Earley, 1918). They knew that they had had all the training available, all the luck and well wishers hoping they prospered but it was out of their hands and what was going to be was just going to be. Upon reading these letters tonight, I have never particularly noticed this theme in the letters, but tonight of all nights, it has rung more true to our 10 girls theatre company than ever before. The show has had all the rehearsals possible, we have our families, friends and loved ones wishing us well, sending us messages of luck and belief and now it is out of our hands and tomorrow night: what will be will be.

Works Cited

Frank Earley, ‘Pray for me’ (1918).

Ted Poole, ‘Becoming a Man’ (1918).

Will Martin, ‘Forever Sweethearts’ (1917).

All above accessed on http://aggsliterature.wordpress.com/wwi-letters-home/ on Thursday 22nd May 2014.

Vaughan, W. McMaster University Libraries. Accessed on May 22 2014, http://pw20c.mcmaster.ca/case-study/socks-boys-marion-simpson-and-knitters-first-world-war